How do we unpack the levers for behaviour change? A simple framework

How do we inject some more science into our design process, to develop solutions that best fit with how people actually make decisions?

Over the past few years I’ve worked with a range of teams and companies operating in different sectors to better understand why their customers do what they do, and how we can engineer better experiences – for the user and organisation. And I’ve noticed that the growth in interest in behavioural science as a core part of a designer’s toolkithas been phenomenal.

Concepts such as ‘people don’t do what they say’ or that our behaviour can be influenced by factors outside of our conscious awareness seem to be well accepted. In fact, more and more I’m finding that people are aware of researchers such as Daniel Kahneman or Dan Ariely , or can use terms such as ‘ System 1/ System 2 ’ and ‘ heuristics ’.

The interest is there. The willingness to probe into the psychological levers of behaviour is there. Is something missing?

From my experience, the challenge is in application – taking well-proven concepts and applying them in a systematic way as part of the design process. Done well, behavioural science can support a designer’s understanding of their user and lead to better, and even counter-intuitive, design solutions.

But to take advantage of scientific fields such as psychology and behaviour economics (yielding 4 million+ and 3.3 million+ references, respectively, on Google Scholar), there need to be some guidelines. Guidelines that help guide your path without spoiling the creativity of designing for people.

For a view on why designers should be interested in bringing more behavioural science into their repertoire, see a previous article How can behavioural science contribute to better design decisions?

A simple framework for understanding behaviour change

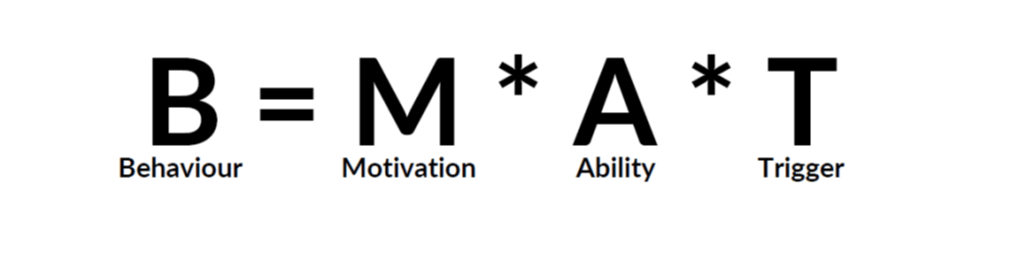

When trying to understand why people do what they do, and how to design for behaviour change, there are a number of frameworks that can be utilised. One that I’ve found useful in a range of situations is the B=MAT (or B=MAP ) model developed by the behavioural scientist BJ Fogg from Stanford University.

Figure 1: The B=MAT model for understanding behaviour change.

It explains “that three elements must converge at the same moment for a behaviour to occur: Motivation, Ability and a Prompt”. When someone is motivated (M) to behave in a certain way, has the ability (A) to behave in a certain way, and the right trigger (T) converges then a behaviour (B) can occur. It’s proven useful for understanding for what and why people are currently behaving in a given way, and what might be changed in the future.

The key benefit I find with this model is it stretches people’s thinking beyond what is immediately in front of them (e.g. what users claim to be important in interviews). As an example, in a recent project I used this model to help reframe the problem from one of awareness of the proposition’s benefits, to one in which the key trigger to make use of the proposition wasn’t cutting through into people’s awareness. Making the trigger more salient and obvious was a simple solution – and one which didn’t immediately surface in the team’s thinking.

An example: Understanding reluctance to wear masks in public

To illustrate how this approach can be applied, let’s take the issue of mask wearing in public spaces such as supermarkets and buses. In a recent project I’ve been involved with (The 2020 Vision Project) looking at how New Zealanders have responded to COVID-19 and the several waves of lockdown, people’s reluctance to wear masks in public settings proved to be an interesting challenge.

Why? Because most people accepted that it was a necessary behaviour, to help the ‘Team of 5 million’ combat COVID-19 – supported by frequent exhortations from people such as Jacinda Arden to “make it [wearing masks] a part of normal life”. But there were also plenty of people who were reluctant to wear them in public at first due to concerns about what others might think: “My theory is that the minute I want to shop … the mask should go on … but I look around at what others are doing”

This led to two challenges:

- We found broad support with the idea of wearing masks in public, but reluctance to wear them as it was a new and weak social norm coming up against a strong existing social norm. For example, data from survey research firm Dynata found that only 45% of Aucklanders during Level 3 in August 2020 reported always wearing a face mask in public locations

- There was a belief that retailers and supermarkets needed to control the safety of the store environment, including controlling the behaviours of other customers. Another survey conducted by Dynata found that 63% of people supported mandatory mask wearing in supermarkets and 64% at malls

So if you were a retailer caught in the middle, how might you address this issue, where people knew what they should be doing, but weren’t, and expected you the retailer to keep control of the store environment?

Here’s how you could unpack this using the B=MAT model, and come up with a range of different solutions:

Motivation:

What are people motivated to do (or not do)?

- Social pressure can exert a strong promoting and inhibiting pressure on how we behave

- In this situation, could we highlight the desired behaviour, or make it the default behaviour to normalise it? For example, signs saying “Thanks everyone for wearing their mask”

Ability:

What are people able to do (or not able to do)?

- Ability is more than just the skills and knowledge to undertake a behaviour, but also the capacity to perform the behaviour at that point in time. In this case, do people have a mask to wear at the point they enter the store?

- Could we hand out masks to people on the way into a store, or have them on offer next to the entrance? This reduces expectations and effort on behalf of customers

Triggers:

What triggers do people see (or not see)?

- A trigger can exist to increase people’s motivation, raise someone’s ability or to remind people in the moment to change their behaviour

- Could we use visual triggers (e.g. shop displays and images with people wearing masks) to reinforce a new social norm? Or even a simple command as someone walks into the store (“Now’s the time to put your mask on”)?

Are these three factors aligning at the right time?

- Quite simply, are the right messages and prompts occurring at the time necessary to impact behaviour

- For example, signs saying to “remember your mask” might be too late outside the store, but might be a good reminder as people leave their car, assuming there is a mask in the glove box

This is quite a simplified example but is a nice way of demonstrating how taking a different lens on what people are doing and why that might be the case can yield different results. In practice, this approach tends to stretch team’s thinking when conducting user research and encourage them to come up with different types of solutions.

Is this the one user behaviour model to rule them all?

Unfortunately, not even close. There’s a range of models that are worth pulling out in different situations, that can yield different solutions and ways of thinking. But like my Master’s supervisor said: “All models are wrong, but some are useful”.

For me, this model continues to be a simple and useful lens on people’s behaviour in a range of situations.

Note: For anyone who wants to go deeper into this topic, I’d highly recommend visiting BJ Fogg’s

Behavior Model site