Is there anything in your life that you do repeatedly, whether that's monthly, weekly or several times a day, that you do a certain way? Something you do on autopilot, without a lot of thought?

Of course there is.

Have a think about these tasks - do you follow the same routine every time?

- Doing a

weekly supermarket shop

in store - do you tend to buy the same brands of food, shampoo etc. each time? Explore the store in the same way?

- Which

stores do you visit

– is it the same supermarket? Petrol station? Café on the way to work?

- Putting your

shoes and socks

on - are you a sock/sock/shoe/shoe person or a sock/shoe/sock/shoe? Do you always start with the same foot?

- Doing the dishes - do they pile up on the bench, or in the sink? Do you rinse before putting them in the dishwasher? Does the dishwasher go on at the same time each day? Do you empty it straight away or when you're next getting a meal prepared?

For the tasks we've mentioned above, there is no right or wrong way to do them. If your pantry’s stocked, your car is topped up with petrol (unless you’ve taken the socially minded EV route), you've got your shoes and socks on and a kitchen of clean dishes* - you've succeeded. But the way we each go about doing these tasks is generally so engrained in us, that we do them without thinking.

*We do acknowledge the many domestic arguments that can come from different household members having a different routine for these tasks. If you're a 'dishes do NOT go in the sink' person living with a 'dishes go in the sink until I'm ready to deal with them' person, I feel you. ^SG

And that’s great. By performing these tasks on autopilot we’re able to direct our attention – and our limited headspace – to more important topics.

Imagine now you're a retail store, trying to change the way people walk around your shop, a contact centre manager, trying to get your team to reduce call handling times by a few seconds, or an FMCG brand trying to increase purchase of your products. Or maybe you work hard all day, you're tired and you just don't want to see a sink full of dirty dishes when there is an empty dishwasher waiting nearby.

In each of these situations, you're trying to change someone's behaviour, and likely to come up against someone’s existing habits.

So what is a habit?

Essentially, a habit is a behaviour that you perform in the same way, in response to specific situations every time. It’s an automatic and inflexible response, and although it may have started out as a choice, it’s become an engrained habit through repetition.

When you first performed the behaviour, it would have taken more brain power and thought, but through the repetition, over time, the behaviour is now performed with little conscious thought.

How do habits get formed?

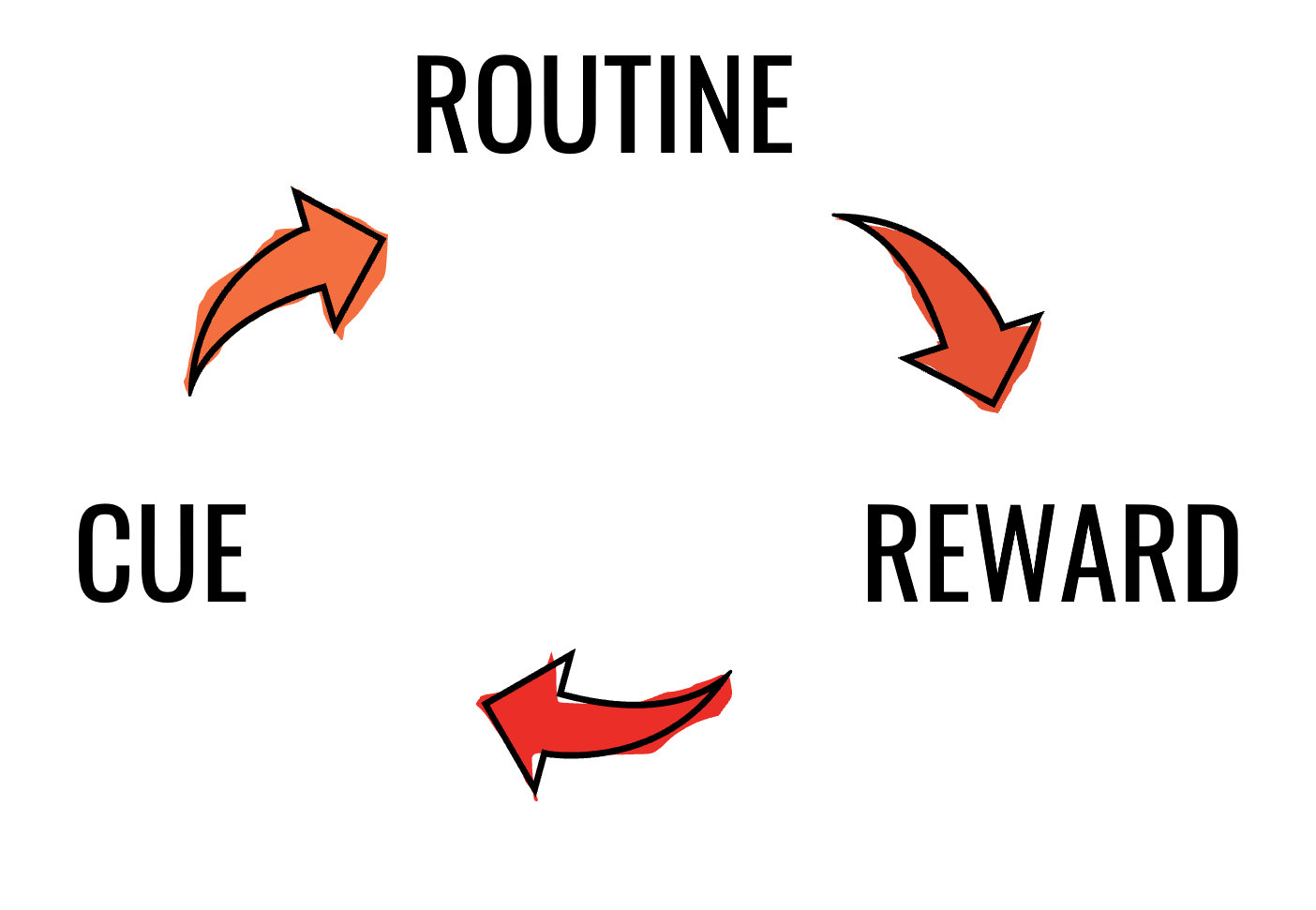

Charles Duhigg, an American writer, coined 'the habit loop' in his 2014 book 'The power of habit', from a simple neurological loop discovered by MIT researchers. The idea is that there are three key stages involved in forming every habit, and once you've identified each component, you can then start to work on changing the habit.

What are the challenges of habits?

The key challenge of habits - for anyone wanting to change one - is that they occur subconsciously, and they can occur long after their utility has waned. As an example, I once did a lot of training to complete the NZ Ironman (2015 … it was before kids), which required a lot of food intake. Unfortunately, after Ironman – when I stopped training – the food habit continued and my weight ballooned.

The habit continued long after the requirement for all those extra calories had disappeared.

From a different perspective, I recently moved house and now have a 10min walk to a ferry terminal. This ferry could take me across the water to Hobsonville Point, a new suburb in which several members of my family live. While I knew the ferry was there, by habit, I consistently put my kids in the car and took a much longer commute to visit family. It wasn’t an issue of awareness, it was a habit that had outlived it’s usefulness.

How do you create a new habit?

The idea behind the habit loop is that once you have identified what triggers the behaviour, the reward it provides, and the behaviour itself, you can begin to adapt it. Through experimentation you can find a behaviour that triggers the same emotional response (reward) as the original.

If there is a new habit you want to create - e.g. bringing your lunch to work instead of buying it, or going to the gym every day - you need to create the cue and reward that will set you up for success.

For example, to build an exercise habit could you leave your shoes by the bed (the cue) to trigger a run in the morning (the routine), which finishes at your local café for a coffee (the reward)?

What about breaking a habit?

The approach we've outlined above relies on new habit formation - what if you would instead like to simply break a habit? Perhaps stop customers from leaving clothes on the changing room floor, or stop employees from talking over others and interrupting in meetings.

In this instance, the science of habits would tell us that we should remove the cue that causes our customers or employees to perform the related behaviour, or replace it with a competing cue. Do customers leave clothes on the floor because there aren't enough hooks? Try a clothing bin just outside the doorway. Are employees interrupting because they don't feel they usually get enough time to share their ideas? Try changing the meeting format!

But one of the biggest opportunities is some disruption to our existing routines. Moving house, changing jobs, getting married or having a child, as examples, are all changes that might allow us to create new, or replace old, routines.

A good example comes from the UK … during the 2014 London underground strike some, but not all, of the networks underground stations were forced to close. This meant some commuters were forced to look for new routes while others were able to continue as normal. After strikes finished,

5% of disrupted commuters continued with their new routines – the new habit had stuck.

Perhaps that’s why we’re seeing some organisations coming through the past two-years of COVID disruptions (e.g., lockdowns, working from home) stronger. Through intent or luck, they’ve been able to align themselves with the new habits of their users.

Want to know more?