Inattentional blindness: Why a gorilla on a basketball court explains why no one saw your brand

Earlier this week I was talking to an old colleague about the latest advertising campaign they worked on. Media spend was relatively high but the latest tracker results had come in – and attribution was disappointing. I tried to reassure him that other brands had similar issues – I’m not certain it was that reassuring!

Why?

The challenge is that in our busy lives there’s so much info streaming past our eyes that never gets picked up – in fact much more than we realise. We’re focused on other tasks; we have other goals we’re trying to achieve. In short, there’s a lot going on. And of course, we’re not aware of what we’re missing. (As an example, one study found that only 18% of ‘viewable’ online adverts were actually seen by people).

The busyness of our lives can lead to something called inattentional blindness – one of the most entertaining ideas presented to first year psych students. What is it?

Watch the video below for an explanation.

WARNING: DON’T READ ON WITHOUT WATCHING THE VIDEO BELOW

The disappearing gorilla – that never disappears

Our mind’s a powerful thing – it pulls together a lot of different information to help us understand an amazingly complicated world. And sometimes it’s ability to focus attention on a task can make it blind to some pretty important bits of information – such as a gorilla walking across a stage and beating its chest.

The psychologists Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris demonstrated inattentional blindness in this now infamous experiment. By getting people to selectively attend to the people passing the basketball, they were able to blind people to something that in hindsight was obvious. Similar studies have shown this can also occur for auditory info.

Why? There are limits to our attentional capabilities – and when it’s overloaded or focused on something, it has to restrict the attention it gives to other information. Even if it’s a gorilla walking through the centre of your screen.

Commenting on the finding, Simons says:

"Although people do still try to rationalize why they missed the gorilla, it's hard to explain such a failure of awareness without confronting the possibility that we are aware of far less of our world than we think”

As an aside, Simons and Chabris did a follow-up video with similar results.

Inattentional blindness and advertising

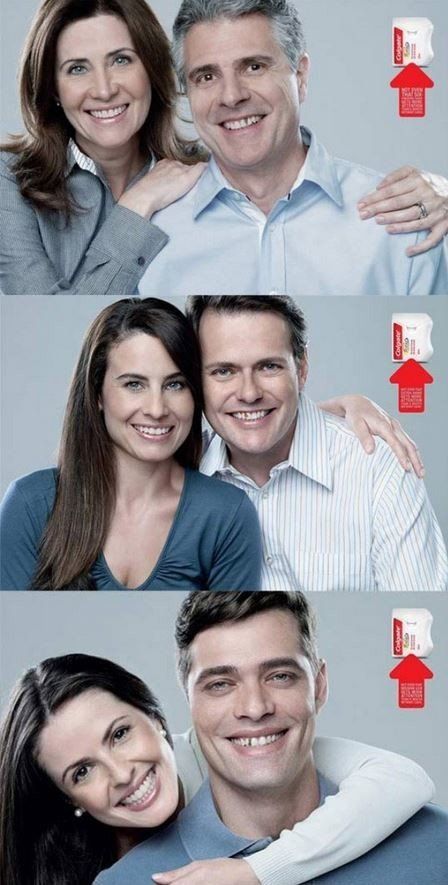

A 2012 Colgate from Y&R Brazil takes advantage of people’s inattentional blindness in these dental floss adverts.

Did you notice anything unusual about these images? How about the fact that in the first image, the woman has too many fingers on her left hand? Or the phantom arm on the man’s shoulder in the second image? Or the missing ear on the man in the second image?

This campaign (tag line: “'Not even that [insert anatomical oddity] gets more attention than a mouth without care”) demonstrates that when people’s attention is focused on something, it can miss a whole lot else.

A more concerning insight comes from several bits of research I’ve been involved with over the past 18 months. Using eye tracking to find out what elements of NZ TV adverts viewers actually see, it’s become clear how few people notice key branding elements because attention is being focused on other story elements or bits of info (e.g. websites, products). Essentially the advert is competing with itself for viewer attention, and branding loses out.

What does this mean for advertisers?

Beware of the limits of your customer’s attention – and if you want them to remember who you are, try not to overload them with other tasks and story telling elements. Otherwise, your brand will be the gorilla on the court.

This article was first published by Cole Armstrong on LinkedIn in May 2019.