Why Santa needs some Choice Architecture

What makes Choice Architecture particularly powerful, is when “choice architects” utilise the latest findings from behavioural science – in a deliberate, rigorous way – to influence behaviour. Research has shown that people’s behaviour is more predictable than we many people realise; and that the influences on our behaviour can’t always be detected by asking people what affects their decisions, but by observing what people actually do and how they respond.

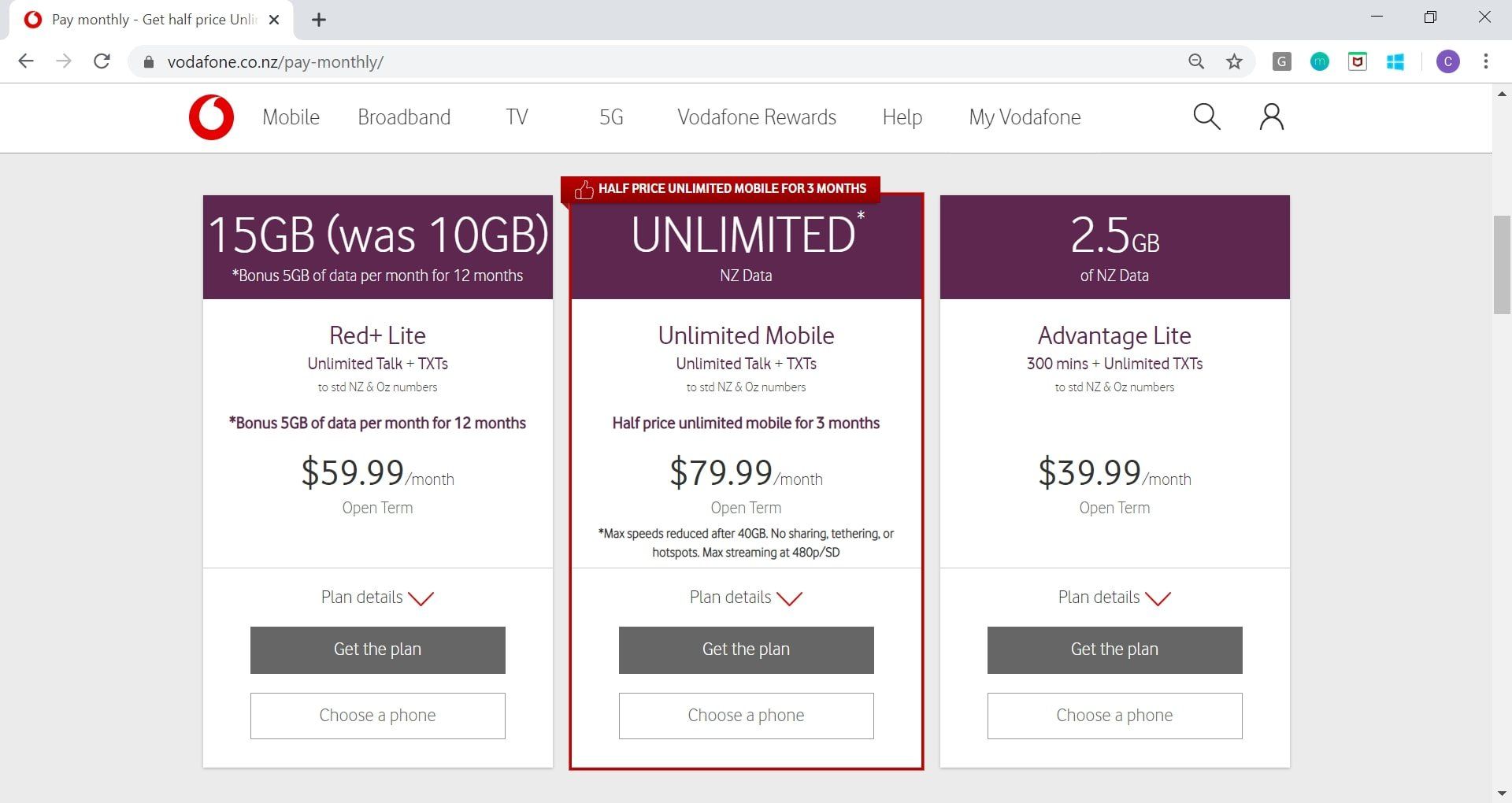

Salience: Making the desired option the most visually obvious

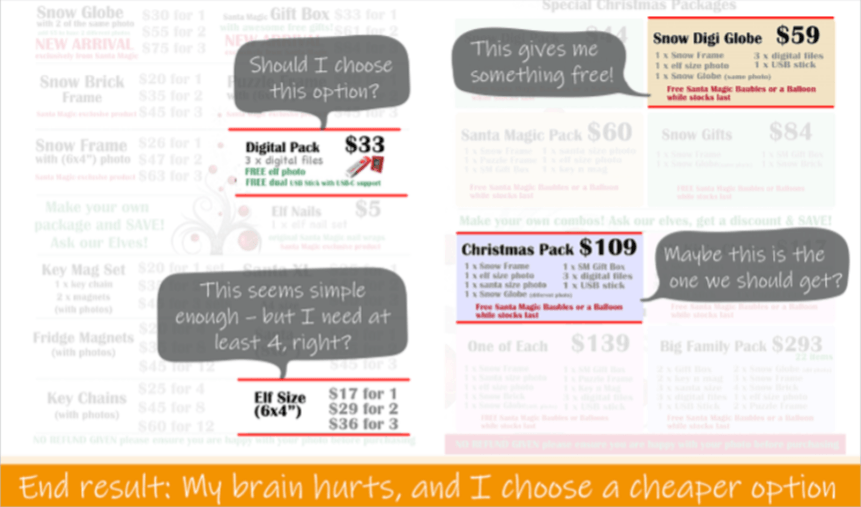

One of the simplest solutions is to make the most desirable choice stick out on the page. This can be done through use of imagery, borders, font size and colour, amongst other options. This stems from the fact that the brain is inherently lazy – with a preference for the option. Making the option more salient doesn’t just increase attention, it makes the option easier to process..

For example, Vodafone guides people towards a preferred mobile option, Unlimited, by changing the outline colour to make it more salient. NB: this also works because they’ve focused on one option, instead of highlighting multiple competing options..

Social proof

When making decisions, we are heavily influenced by the decisions of those around us. By utilising social proof we can indicate what a typical decision is and increase the likelihood that a customer will make a similar decision.

For example, in this situation Santa’s photographer could have indicated which option is their most popular option (assuming that’s the option they want to promote), or which is their most popular option amongst a certain type of customer. We were a family of three – what option would most families our size have chosen? We’ve got three sets of grandparents and a range of uncles and aunties we might want photos for – what do people in a similar family dynamic choose?

Decoy product

Another option that may have worked is through the use of decoy products – the inclusion of a similarly priced but inferior choice that makes you away from choosing a lower value option and makes the higher priced option seem like a better deal. This works because value is a subjective experience and is based in the context in which a decision is made. Change the context, and you can change someone’s perception of value.

Perhaps one of the 43 photo packages could have acted as a decoy product to a more expensive product offer?

Anchoring

How do we know something is good value? Obvious really – we evaluate what we get for what we pay against some other value that springs to mind. Anchoring works by deliberately being that anchor value that springs to mind – for example a $5 coffee sounds great given that I’m anchored to pay $5 for coffee in most cafes. A $7 coffee sounds like more dubious value – unless I’m sitting in an airport or at a café overseas where the coffee around me costs an average $7.

This effect has been famously documented by behavioural economist Dan Ariely, using the example of The Economist subscription. In this example, the inclusion of an inferior subscription offer – an offer that few people chose – would have resulted in an increase in revenue of 43%. The inferior subscription offer wasn’t intended to be chosen, but merely makes a more expensive subscription offer appear to be better value and hence more desirable.

In this case, they might’ve anchored me by pointing to the cost of a typical family photo sitting (say $200).

Summary

Some of these examples are more plausible than others. What would make the difference is taking control of the Choice Architecture – being very deliberate about what is presented and presenting in a way that works with how our minds actually make decisions. If employed correctly this can be a win for customers who get a better experience and feel better about their choices, and a win for the organisation who is bringing in greater revenue for existing resources.